|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The Royal Family, the Nazis, and the Second World WarThe Royal Family in the 1930's During the 1930's most members of the Royal Family were living in southern Bavaria. On account of an agreement with the Bavarian state government in 1923, the Wittelsbachs had retained corporate ownership of a number of properties including several palaces and castles as well as large tracts of forest and agricultural land. They also retained a right of residency in several other palaces and properties owned by the Bavarian government. Members of the extended family had apartments in several residences. They moved back and forth among these residences depending upon the time of year and upon their various engagements. King Rupert and Queen Antonia's official residence was the Leuchtenberg Palace. Its prominent location in central Munich was a symbol of Rupert's continuing importance in Bavarian public life. It was here that he had been born in 1869. The palace provided plenty of space for Rupert and Antonia's six children: Henry (born 1922), Irmingard (born 1923), Editha (born 1924), Hilda (born 1926), Gabrielle (born 1927), and Sophie (born 1935). Important family celebrations such as weddings were held at Schloss Nymphenburg, the royal summer palace on the outskirts of Munich.

For some years the royal family had spent their summers at Schloss Berchtesgaden on the Bavarian side of the border with Austria near Salzburg; Princesses Irmingard, Hilda, and Gabriele had been born there. In 1933, however, Rupert discontinued his summer visits to Berchtesgaden; he wanted to avoid any encounters with Adolf Hitler who had a summer home in the area, and who that year had been appointed Chancellor of the German Reich. Henceforward, Rupert and his family spent their summers at Schloss Hohenschwangau in the Bavarian Alps; this castle is famous as the childhood home of King Ludwig II of Bavaria who built Schloss Neuschwanstein only a few miles away. About 25 km southwest of Munich the royal family maintained a home at Schloss Leutstetten. This large manorial house was at the centre of a farming estate bought by Rupert's father in 1875. In addition to the castle itself there were also several smaller houses where various aunts and uncles lived. Of all of the royal family's residences, Leutstetten was the one most like a home. Rupert's son from his first marriage, Albert, lived with his wife Marita at Wildbad Kreuth, a country estate about 50 km south of Munich. They had four young children: Marie Gabrielle and Marie Charlotte (twins born 1931), Franz (born 1933), and Max (born 1937). Wildbad Kreuth was owned by Albert's uncle, Duke Ludwig Wilhelm in Bavaria. Here Albert developed his interest in the management of deer stocks.

Rupert's younger brother Franz and his family lived most of the year at Schloss Sárvár. This large estate in western Hungary had been inherited by Rupert and Franz's mother Queen Mary IV and III. Rupert's sister Maria and her husband the Duke of Calabria (head of the Royal House of the Two Sicilies) lived at Villa Amsee in Lindau on the shores of the Bodensee. Rupert's unmarried sisters Hildegard and Helmtrud lived at Schloss Wildenwart. This castle (today the country residence of Prince Max) is located about 60 km southeast of Munich; it had originally been purchased by Rupert's great uncle King Francis I.

Rupert and the Rise of Naziism King Rupert had a long history of opposition to the Nazis dating back to Adolf Hitler's first attempt to seize power in 1923. At that time the social-democrat government of the German Weimar Republic was weak and unpopular. In Bavaria the Royal Family had retained its widespread popularity. Monarchist sentiment was particularly strong among those who opposed the federal German government and favoured a stronger, even independent, Bavaria. The many right-wing groups which rose up to oppose the threat of Communism also found it useful to claim the monarchist banner for themselves. A number of monarchists were associated with these right-wing groups, seeing in them a preventative against Communism and a first step towards a monarchist restoration. Among these right-wing groups was the National Socialist German Workers Party headed by Adolf Hitler. On November 8, 1923, at a meeting of prominent conservatives in Munich, Hitler staged a coup d'état, subsequently called the "Beer Hall Putsch". Hitler claimed that he intended to restore the Bavarian monarchy; indeed that is how the coup was reported in The New York Times. Rupert, however, had not been consulted beforehand, and refused to support the coup once it had started. Rupert wanted to be king of an entire nation, not just of one political faction. Nor was he willing to take the throne by force of arms. The coup collapsed, and Rupert gained the eternal enmity of Adolf Hitler who was imprisoned for one year. The Nazi Takeover In the early 1930s Germany was in a state of political crisis. There were a host of political parties, none of which commanded a majority. There was an ever-present threat of a communist take-over. The Nazis had turned their priorities to the electoral system. Owing to their nationalistic and anti-Communist propaganda, they had become the most powerful single political party in Germany. The monarchist movement in Bavaria was also undergoing a revival. In November 1931 Rupert issued a proclamation which thanked Bavarians for their acknowledgement of the tenth anniversary of the death of his father King Ludwig III of Bavaria; in this proclamation Rupert described himself as his father's "heir, destined for his rights and duties". By 1932 the Nazis had the support of almost half the German electorate. There was every reason to believe that if Hitler were named German chancellor (prime minister) the next step would be for the Nazis to establish a permanent dictatorship. The state government in Bavaria feared that the the federal German government would dismiss the elected government of Bavaria (as actually happened in Prussia in July 1932). In May 1932 the Bavarian Minister-President (premier) Heinrich Held met with Rupert's chief political advisor Baron Erwein von Aretin. Held wanted Aretin to prepare for a monarchist restoration in Bavaria, but was unwilling to have his government publicly endorse the plan. In January 1933 Held and the Bavarian government began to consider the idea of naming Rupert as General State Commissioner. This temporary office was intended to be used in times of crisis; it gave the holder extraordinary powers to restore law and order. Such an appointment would have been a clear sign of resistance to Hitler who was appointed German chancellor on January 30. At a meeting in the Leuchtenberg Palace on February 21 Held intended to announce Rupert's appointment - but at the last minute he wavered, and no announcment was made. Rupert did not give up hope of averting a Nazi dictatorship. The German President Field Marshal von Hindenburg had always been a fervent supporter of an eventual monarchist restoration. Rupert sought an assurance from him that the federal government would not use military or economic means to oppose a restoration of the monarchy in Bavaria. Hindenburg, however, believed that the Nazis offered the best hope for Germany's future. On March 9 the federal German government (now controlled by the Nazis) appointed the Nazi Franz von Epp as Reich State-holder in Bavaria. Like General State Commissioner, this was an extraordinary office designed to restore law and order; the difference was that it was an appointment of the federal (Nazi) government instead of the Bavarian state government. Almost the first action of the Reich State-holder was to dismiss the elected government of Bavaria. Rupert sent letters of protest to President von Hindenburg calling upon him to support the rights of the state governments. Rupert even wrote to the exiled German Emperor asking him to intervene. Once the Nazis were in power, they immediately began to remove any dissent. Rupert's closest political advisor Baron Erwein von Aretin was imprisoned at Dachau. In May the monarchist youth organisation was forcibly incorporated into the Hitler Youth. In July, the King and Country League, the major monarchist group in Bavaria, was dissolved. Rupert himself was very soon excluded from public life in Bavaria. In the past his birthday had been openly celebrated each year; but this ceased after 1933. In 1933, 1934, and 1936 there were plebiscites in Germany for the general population to show their approval of the Nazi takeover. It was widely reported that on these occasions Rupert and Antonia had refused to cast their votes. Rupert determined to ride out the storm; he did not know that things were to get much worse. Rupert decided that his younger children would be educated in England. This avoided Henry being a member of the Hitler Youth or his sisters being members of the League of German Girls. In 1936 Irmingard and Editha were sent to the Convent of the Sacred Heart School in Roehampton (now Digby Stuart College at Roehampton University). Hilda and Gabrielle joined them there a year later. In 1938 Henry began his studies at the University of Oxford (he was only sixteen). In order to avoid membership in the Nazi University Student Corps, Rupert's nephew Ludwig (elder son of Rupert's brother Franz) withdrew from his university in Germany, and began studies at the University of Budapest. The Beginning of World War II In the summer of 1939 Rupert went to visit his brother Franz at Sárvár in Hungary. His eldest son Albert and his family vacationed in Yugoslavia as guests of the Prince Regent Paul. Rupert's younger son Henry and his four oldest daughters returned from school in England to join their mother and youngest sister for the holidays in Luxemburg. After war was declared, September 3rd, the children spent several weeks at school in Brussels before returning with their mother to Munich. There they were reunited with their father in the Leuchtenberg Palace. The living situation for the royal family was difficult. The Wittelsbach Palace in Munich, where Rupert had grown up, had been confiscated by the Nazi government and was now being used as the local headquarters of the Gestapo. Schloss Leutstetten, their usual country residence, had also been confiscated and was being used to lodge German refugees from the Saarland and the Palatinate. Rupert and his family continued to live in the Leuchtenberg Palace in Munich, but this huge building was impossible to heat on account of the wartime rationing of coal. The Departure from Germany In November 1939 Rupert hoped to attend the seventieth birthday celebrations of King Victor Emanuel III of Italy in Rome. Rupert often attended important royal events; as a frequent visitor to Italy he knew King Victor Emanuel well. Because of the wartime restrictions, however, Rupert was unable to obtain a passport in time for the birthday, but he promised King Victor Emanuel that he would present his congratulations in person several weeks later. Eventually the Nazi authorities determined that Rupert would be less of a threat if he were outside Germany and issued him a passport. On December 31, 1939, Rupert left Germany for Italy. Antonia and her children had to wait several more weeks to receive passports. It was only in February 1940 that they were able to travel to Italy. The children's English nanny, Miss Wright, had had to return to England at the beginning of the war. Countess Paula von Bellegarde accompanied the family to Italy; she had first come to the royal family as a French tutor in the early 1930's and remained with them for the rest of her life. Rome In Rome, Rupert and his family were welcomed by the King and Queen of Italy whom they visited at the Quirinal Palace. They also visited Pope Pius XII in the Vatican; in 1921 the pope himself (when still an archbishop) had married Rupert and Antonia in Bavaria. Rupert had been a frequent visitor to Italy in previous years. Here he indulged his passion for art and art collecting. Now he was able to introduce his children to Rome. He took them to the catacombs, the Colosseum and other Roman ruins, and the many galleries of Renaissance and baroque art. The royal family lived briefly at the Hotel Eden near the Pincio; but the expense of this luxury hotel could not be supported for any length of time. The education of the children (now aged from four to seventeen) had to be continued. The family owned no properties in Italy and could obtain no funds from Germany to purchase any. But they had many friends and distant relatives in Italy who were generous in their support. Florence The royal family moved first to Villa Bellosguardo in the hills just a few miles outside Florence, another city already well-known to King Rupert. The villa was owned by Baron Giorgio Franchetti and his German wife, Baroness Marion von Hornstein (sister-in-law of the painter Franz von Lenbach who had done several commissions for the royal family); Rupert had previously stayed at the villa in 1937. Irmingard and Editha were sent to the school operated by the Sisters of the Sacred Heart in Villa Lante on the Janiculum Hill overlooking Rome. Here they learnt Italian for the first time. Their tuition was paid by their aunt Grand Duchess Charlotte of Luxemburg, but in May 1940 Germany invaded Luxemburg, thus removing this financial support. In March 1940 Henry turned eighteen, the age at which he was required by German law to report for military duty. When he reported to the consulate in Bolzano, he was informed that he would not be permitted to return to Germany. At the same time Rupert's request for a pass to allow him to return to Germany was turned down. In fact it was advantageous for both Rupert and the Nazis that he and his family remain in Italy; both were playing a propaganda game. The Nazis could claim that the Wittelsbachs were not patriotic; equally Rupert and his family could claim that the Nazis had refused their re-entry to Germany. The royal family now had to make plans for a more permanent stay in Italy. Rupert moved to an apartment in the Palazzo Pecori-Giraldi (the home of the Bavarian Baron Theodor von Fraunberg and his Italian wife Countess Adriana Pecori-Giraldi). This building on the south side of the River Arno in Florence would be Rupert's principal residence for the next five years. For most of that time Henry lived in the same apartment while he studied law at the University of Florence; Irmingard also lived here on occasion. Antonia and her younger daughters moved to a pensione only a few blocks away on the north side of the river. For the next four years this was their home whenever they were in Florence. Albert's Family Meanwhile Rupert's elder son Albert had also managed to escape from Germany. In 1939 he took his wife Marita and their four young children to Hungary. They lived briefly at Vép, the home of Prince Laszlo Esterhazy who was married to Marita's cousin Countess Maria Erdödy; Vép is only about twelve miles west of Sárvár where Albert's uncle Franz lived. At the end of September 1939, the family moved a hundred miles east to Budapest. There they rented a furnished flat owned by another of Marita's distant cousins, Countess Eduardine Zichy (born Markgräfin von Pallavicini). Family Travels The climate of Florence was not conducive to Antonia's health. She soon moved with her daughters and Paula von Bellegarde to the Dolomite Alps near the Italian-Austrian border. They stayed first at Bressanone where the princesses were sent to the school of the Loreto sisters (called in Italy the "English Ladies"). They were joined there at Christmas by Rupert and Henry. The mountains in the area provided much opportunity for outdoor sports; Antonia and her children loved to ski and to climb.

The summers were spent at Forte dei Marmi. Many years ago the artist Adolf von Hildebrand had introduced Rupert and his first wife Marie Gabrielle to this seaside resort northwest of Pisa. Antonia and her children vacationed here, often with other relatives including her great aunt Duchess Marie-Jose in Bavaria (Albert's grandmother), her sister the Princess Schwarzenberg, and Rupert's cousin Donna Fabiola Massimo and her children. In spite of the fact that Rupert, Antonia, and their children lived separately, they often saw each other. Even Albert managed to visit them from Hungary; in 1942 he came with Antonia to Padua where Irmingard had been sent to continue her studies. That summer Rupert went to Switzerland for two months for medical treatment. In February 1944 Antonia returned to Florence. Since the Nazis and the Italian Fascists were now in control of all of central and northern Italy, Rupert wanted his wife and daughters to move to a Salvatorian convent on the Janiculum Hill outside Rome; there they would be in easy reach of the Vatican in case they needed to seek refuge from the Gestapo. But Antonia feared the heat of a Roman summer, and insisted on returning north to the Dolomites.

On April 18 Antonia with her three youngest daughters and Paula von Bellegarde returned north to San Martino di Castrozza. Editha (now almost aged 20) stayed in Florence with the Franchetti family at Villa Bellosguardo; she was in love with an Italian, Tito Brunetti, whom she married two years later. Irmingard was invited to spend the summer holidays at the home of Princess Gabrielle von Ratibor on Lake Garda. Rupert Evades the Nazis Rupert knew that at some point the Nazis would take action against him. One of his friends, an Italian colonel named Grammacini, was arrested by the Gestapo; he had known Rupert since 1919 when he had come to Munich as part of the peace negotiations. The Gestapo had intercepted one of Rupert's letters in which he discussed the possible effect that Allied bombing of the Walchensee dam would have on southern Bavaria. The Gestapo used this letter to claim that Rupert had special knowledge of the Allies' plans; they beat Grammacini in the hope that he would provide evidence against Rupert. On June 19, 1944, Rupert secretly transferred his Florence residence to an apartment in Via della Mantellate; the story was circulated that he had gone for the summer to Merano in the far north of Italy. Rupert spent 58 days in hiding, exercising inside, reading, and playing cards. On August 14 he presented himself to the British Army which had occupied Florence the previous day. Meanwhile Henry had also escaped detection by the Nazis. He hid in the Palazzo Lancelotti in Rome until the city was occupied by the Allies on June 4. After the Allies entered Florence in August 1944, Henry returned there and was reunited with his father. On August 26 the American military governor of Tuscany, Major General Edgar Erskine Hume, met with Rupert. They had known each other many years before in Munich after World War I; General Hume was of Scottish ancestry and had always shown an interest in Rupert's Stuart descent. Rupert would have travelled to Rome immediately, but in September he became sick; he was now 75 years old. He spent a month in a clinic in Florence where he was visited twice by his nephew-in-law Crown Prince Umberto of Italy. Then on November 1 General Hume drove Rupert to Rome. He stayed at the Palazzo Quirinale, the official royal residence, and had an audience with Pope Pius XII. Rupert had planned to stay in Rome, but his presence there became embarassing for his host the Crown Prince of Italy. The government in London expressed concern that "a German" was a guest of the Italian royal family, and the Italian republicans used this as anti-monarchist propaganda. So on November 10 Rupert returned to Florence where he remained for the next ten months. Arrest and Detention The rest of the royal family had not been as fortunate as Rupert and Henry. On July 20, 1944 there was an unsuccessful attempt to assassinate Adolf Hitler. In the following weeks several thousand people suspected of opposing the Nazis were executed and thousands more arrested. On July 27 the Gestapo took Queen Antonia and her three youngest daughters into custody together with Paula von Bellegarde. They were interrogated about the whereabouts of King Rupert, but fortunately they did not know anything. Editha was also arrested in Florence and brought to her mother and sisters at San Martino di Castrozza. There they stayed until in August they were moved several kilometres to Alpe di Siusi and then to Plan de Gralba. In spite of the fact that Antonia had fallen ill with typhus fever, she and her daughters were transported by train to Innsbruck. Antonia was left in a hospital there while her daughters and Paula von Bellegarde continued to Weimar. From there they were transported north, arriving on October 13 at the Oranienburg-Sachsenhausen Concentration Camp near Berlin. They were registered under the surname "Buchholz" and assigned to one of a number of small houses in the camp which were used for prominent prisoners. Each of these houses was surrounded by a high wall topped with electric wire. Albert and his family had also fallen prey to the Nazis. They had remained in Hungary throughout the war. In November 1943 Budapest was becoming unsafe on account of the Allied bombing. Albert's wife Marita had a cousin Count Peter Erdödy who invited the family to move to Somlovár Castle about 25 miles southeast of Sárvár. On October 6, 1944, Albert, his wife and four children were all arrested there. They were transported to the Oranienburg-Sachsenhausen Concentration Camp and placed in a house immediately next to that occupied by Albert's four half-sisters. Eventually the door in the wall between the two houses was opened and the entire family was reunited. At the end of January 1945, they were joined by Irmingard. At first they did not recognise her; she had lost all her hair. Irmingard had been arrested by the Gestapo at Lake Garda. Because she too had typhus she was sent to the same hospital in Innsbruck where her mother was staying. From there mother and daughter had been transported to another hospital in Seefeld. At Christmas Antonia was well enough to attend midnight mass - and so the medical staff decided that she and Irmingard could be sent to a concentration camp. They took the train north to Weimar in Saxony, but at this point, without any explanation, they were separated. Antonia became sick again and had to be sent to a hospital in Jena southwest of Leipzig. The American army entered Jena on April 13. Antonia was eventually found by a military officer from Luxemburg. Her brother-in-law, Prince Felix of Bourbon-Parma (husband of Grand Duchess Charlotte), came and took her back to a hospital in Luxemburg; when she arrived there, she weighed only 36 kilograms. Meanwhile the situation for the rest of the royal family had deteriorated. At the end of February, with the Russian Army closing in on Berlin, Albert, his wife, children, and sisters were informed that they must move again and that they would be taken to a private house in the Bavarian Forest. Instead, they were moved to the Flossenbürg Concentration Camp near Regensburg. Instead of having two houses in which to live as at Sachsenhausen, all twelve of them were housed together in two rooms in one of the barracks. Their sufferings, however, were not nearly so great as some other concentration camp internees - but they did see everything. On account of the conditions many prisoners died. Their naked bodies were piled up like wood next to the barracks where the royal family were living. Albert insisted on complaining to the camp commandant that children should not be exposed to such sights - but this only resulted in the family being locked into the barracks. When Albert became ill with dysentery, the commandant allowed the family to live in two rooms of a house outside the camp. On April 8, 1945, they were moved to the Dachau Concentration Camp. There they were housed with the families of the generals who had fought at Stalingrad and the families of those German officers who had been executed for their part in the July 20 plot to kill Hitler. Shortly thereafter the family were moved again. The train in which they were being transported happened to pass near their old home in Leutstetten. At the station in Mühlthal they saw their nineteen year old cousin Rasso, younger son of Prince Franz. He followed them on his bicycle to Starnberg where he was able to speak with them briefly and exchange family news. Albert, his wife, children, and sisters were taken to the small hotel in a village on the Plansee, a lake near the town of Reutte in Austria. This was only a few miles south of Schloss Hohenschwangau where the royal family used to spend their summers. One day Albert's wife Marita overheard one of their guards saying that they were to be handed over to the Russians. But the situation for the Nazis continued to deteriorate. Gradually the camp guards disappeared. Towards the end of April a group of three French soldiers arrived; they had freed themselves from a prisoner-of-war camp nearby. Finally on April 30, 1945, the Third American Army arrived.

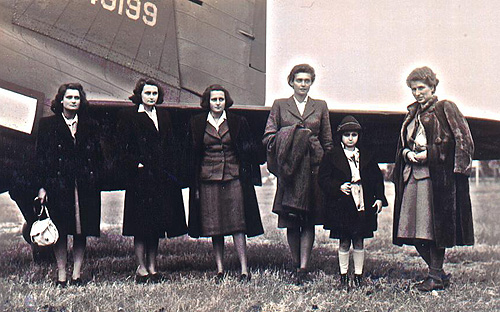

Aftermath Two weeks later an American army officer assisted Rupert's five daughters in returning to Luxemburg. On May 16 he drove them to Schloss Hohenschwangau, then to Schloss Berg, and then to Schloss Leutstetten. Late at night they knocked on the door of the Samerhof, a house owned by the Royal Family across the street from the castle. At the door of the Samerhof the princesses were met by their uncle Franz with his sons Ludwig and Rasso; they had managed to escape from Hungary and to bring with them some of the royal family's famous Sárvár horses. Later the princesses were driven to Augsburg from where they flew to Luxemburg.

In Luxemburg the princesses found their mother Antonia still recuperating in hospital. Several months later Henry arrived in Luxemburg; he and his father had returned to Bavaria in September 1945. Albert managed to get Schloss Leutstetten released to the family through the mediation of an American art expert he knew. Since the Leuchtenberg Palace had been severely damaged by bombing, Rupert sold it to the Bavarian government and made Schloss Leutstetten his principal residence; there he died in 1955. Antonia never spoke about her ordeals, and she never set foot in Germany again; after convalescing in Luxemburg, she lived mostly in Rome and in Switzerland, where she died in 1954. Albert and his family lived at Wildbad Kreuth until they established a new home at Schloss Berg in 1948. Henry worked in New York City where he met a young French aristocrat whom he married in 1951. His five sisters all married between 1946 and 1955. Sources Aretin, Erwein Freiherr von. Kronprinz Rupprecht von Bayern: Sein Leben und Wirken. Weiß-blaüe Hefte 4 (1948). Bayern, Irmingard Prinzessin von. Jugend-Erinnerungen, 1923-1950. St. Ottilien: EOS, 2000. Bayern, Ludwig Prinz von. Discussion with the author, May 2005. Croÿ, Gabrielle Herzogin von. "From my Childhood and Youth". Privately printed. Garnett, Robert S., Jr. Lion, Eagle, and Swastika: Bavarian Monarchism in Weimar Germany, 1918-1933. New York: Garland, 1991. Metts, Albert C., Jr. "A Happy Story". Privately printed. Schlim, Jean Louis. Antonia von Luxemburg, Bayerns letzte Kronprinzessin. Munich: LangenMüller, 2006. Sendtner, Kurt. Rupprecht von Wittelsbach, Kronprinz von Bayern. Munich: Richard Pflaum, 1954. Sweetman, Jack. The Unforgotten Crowns: The German Monarchist Movements, 1918-1945. Ph.D. diss., Emory University (Atlanta, Georgia), 1973. Waldburg zu Zeil und Trauchburg, Marie Gabrielle Fürstin von. Correspondence to the author, April 2005. Weiß, Dieter J. Kronprinz Rupprecht von Bayern: Eine politische Biografie. Regensburg: Friedrich Pustet, 2007. Illustrations Image 1 (The Royal Family, 1935): postcard from my private collection. Image 2 (Albert's children, 1936): postcard from my private collection. Image 3 (At Roehampton, 1938): Irmingard Prinzessin von Bayern, Jugend-Erinnerungen, 1923-1950 (St. Ottilien: EOS, 2000), 200. Image 4 (Skiing at the Sella Pass, 1944): Ibid., 269. Image 5 (Florence, 1944): Ibid., 232. Image 6 (Albert with his children Marie Gabrielle and Franz, 1945): Jean Louis Schlim, Antonia von Luxemburg, Bayerns letzte Kronprinzessin (Munich: LangenMüller, 2006), 136. Image 7 (Princesses at Augsburg, 1945): photograph from the collection of Colonel Albert C. Metts, Jr. This page is maintained by Noel S. McFerran (noel.mcferran@rogers.com) and was last updated July 14, 2010. © Noel S. McFerran 2000-2010. |